Abstract

This review article examines the 15th edition of the Luxembourg Monodrama Festival (June 13–22, 2025), which brought together artists from Luxembourg, Portugal, Belgium, Greece, Croatia, Austria, Burkina Faso, Jordan, the Netherlands, and the Republic of Congo. The festival’s participants explored diverse narrative approaches to monodrama and engaged with the aesthetics and conventions of postdramatic theatre. The performances addressed themes ranging from archetypal human experiences to urgent social and political concerns. Among the issues explored were violence against women, the dual nature of work as both a measure of achievement and a source of psychological strain, mourning in romantic and parental relationships, and environmental degradation. The voices of actors, dancers, musicians, authors, and directors resonated through the universal language of theatre, often self-referential, sharply humorous, and critically engaging, characterized by direct audience interaction and inventive use of stage expression

Keywords: monodrama, performance, diversity, multiculturalism, interaction

This is not the first time we turn our attention to the Monodrama Festival, now in its 15th year, hosted in the welcoming and culturally vibrant city of Luxembourg. This year’s edition took place from 13 to 22 June at the Banannefabrik venue (12, rue du Puits, L-2355 Luxembourg-Bonnevoie).

The banner of the 15th Fundamental Monodrama Festival, 2025

The festival’s founder and artistic director, actor and theatre director Steve Karier, once again fulfilled his mission: to organize an international festival dedicated to solo performances and to promote the performing arts both nationally and internationally. The tangible result of his efforts was a dynamic program of 14 performances by artists from ten different countries over the course of ten days. These included both premieres of works in progress and fully realized, creatively staged monologues.

The diverse perspectives presented in the performances revealed that, both aesthetically/formally and thematically/conceptually, it is quite difficult to identify a common ground in terms of subject matter. Nevertheless, the pressing challenges of our times, combined with the artist’s intrinsic impulse to engage with archetypal aspects of the human experience, resulted in stage works that, both implicitly and spontaneously, entered into dialogue with one another.

For example, gender-based violence was a recurring theme, with woman as both the subject of desire and the object of suppression. The range of depictions included figures of women in the timeless context of love, each asserting her voice and visibility before the other, claiming her right to be respected, each standing as a powerful presence, daring to demand recognition in the arts and in the workplace, and therefore her fundamental dignity.

In Banannefabrik’s two stages, the subject of deviation was also treated in many of its variations. More specifically, the concept of deviation is understood as a psychic symptom, a borderline manifestation incurring social exclusion and incarceration, and also implies the generalized, supreme imperative of professional success and mainstream beauty, as the cause of an agonizing and fruitless struggle.

The common means for portraying these motifs was through the format of the stage monologue, as actors, performers and musicians employed different versions of metadramatic theatre. Here, gaps in the plot development were frequent, narrative fiction interlaced with auto-fiction, self-reference occasioned critical comment and laughter, and commentary on contemporary reality and its norms assumed the guise of ominous clowning. This array of styles, however, is complemented by minimal stage-setting, direct address to the spectator and a brief unfolding of the action.

All the artists participated with enthusiasm in this international theatrical and performative conspiracy of monodrama. They each pursued their own aesthetic and thematic choices in a trajectory which involved social critique and political commentary without self-righteousness and occasionally utilized humor and a pronounced metonymic stage-setting as a back-up.

The Plays

Tu connais Dior?

Text and performance Valerie Bodson. Direction Anne Brionne. Language: French. Luxembourg.

Valérie Bodson. Photo: Juliette Moro

The first performance was delivered by Luxembourg actor and writer Valérie Bodson and directed by Anne Brionne. The work, with its playful and suggestive title Do You Know Dior?, drew the viewer into a confessional journey exploring an issue often understood only in the abstract or at a distance. Over the course of a single day, the protagonist finds herself in the untenable position of losing her home and being forced into homelessness.

Up until that moment, we are told, everything was normal: work, homelife, family and friends. The unexpected crack reveals the invisible world of the social margin and shows how the margin is invisible to the average person. The text, torrential and often playful in its delivery, makes ample use of emotional confession and scathing commentary. The element of surprise is conveyed when she refuses to give herself over to a state of dereliction, adopting as a saving mantra the phrase "I am no good at being unhappy." This slogan operates as a defense mechanism and a reminder of the life she had until recently, but it also urges her to resist the dystopic condition of suffering and lack of community imposed on the homeless person.

Bodson was very consistent in the realistic depiction of her character’s mood changes; she built a rhythm with her voice and body which allowed her to illuminate the range from irony and humor to melancholy and anxiety, while making discerning use of the non-textual components of her monologue. Out of her props – suitcases, a sleeping bag, a tablecloth as decoration of her street bench, the emblematic red Dior handbag of the title – the actor builds a mini universe that is both familiar and unsettling for the complaisant viewer.

Noces

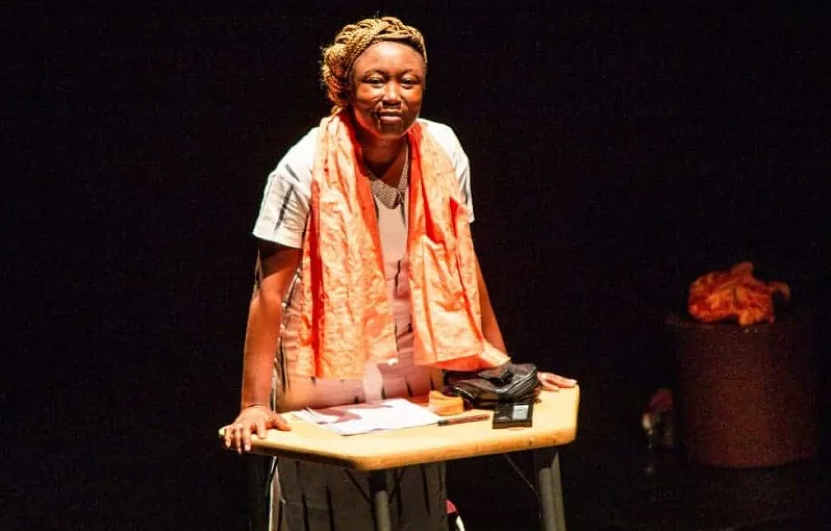

Text and performance Safourata Kabore. Direction Odile Sankara. Language: French. Burkina Faso.

Safourata Kabore. Photo: Emmanuelle Konkobo

The Wedding, written in French, interpreted by Safourata Kabore and directed by Odile Sankara, showcased the powerful bipolarity of trauma and desire, both textually and performatively.

Kabore’s monologue unfolded as a portrayal of the girl, the adult woman, and the future wife, all seen through the prism of a mirror. The impending ceremony awakens memories, reactivates trauma, invokes the need for acceptance and underscores the importance of resisting male power. The future wife, standing in front of the mirror, carefully applies her makeup, which ultimately becomes a mask, a symbol and an expression of cultural identity. She tries on her wedding dress while frequently checking the clock, a constant reminder of the temporal boundary leading up to the wedding ritual, which marks symbolically the transition from recounting a painful experience to embracing the present.

The music and few sparse stage objects provide a dynamic accompaniment that skillfully blends poetic symbolism with the realism of the acting. The direction lucidly conveys how personal testimony embodies the collective voice, calling out the abuses of the past and emphasizing the need to break free from them.

Falsch Beweegungen

Text and performance Serge Tonnar. Language: Luxembourgish. Luxembourg.

Serge Tonnar. Photo: wrong movements

From the first few minutes, the Wrong Moves/Falsch Beweegungen by songwriter, author and performer Serge Tonnar worked very effectively as a sobering wake-up call. His performance took place in the familiar realm of the metadramatic. The mixture of narrative and music, the improvised character in movement and the use of a few eloquent objects such as a black tutu skirt or the microphone in various comical ways created an engaging commentary on imperfection and failure, as these are appraised in our modern world. Tonnar became the embodiment of the wrong moves, defending with humor and ardor the right to diverge from standards of beauty for the human body and unapologetically accept botched personal and professional choices, failures and attempts to make things right or to fail once again.

His guitar and his singing, as intrinsic elements of his performance, provided the coordinates of Tonnar’s artistic identity and excused him from adherence to a particular interpretative genre.

The painted talking belly moving to a strong dance beat, along with the comments on success and disapproval, provided pungent criticism and staged excess at its core.

Requiem for a Clown

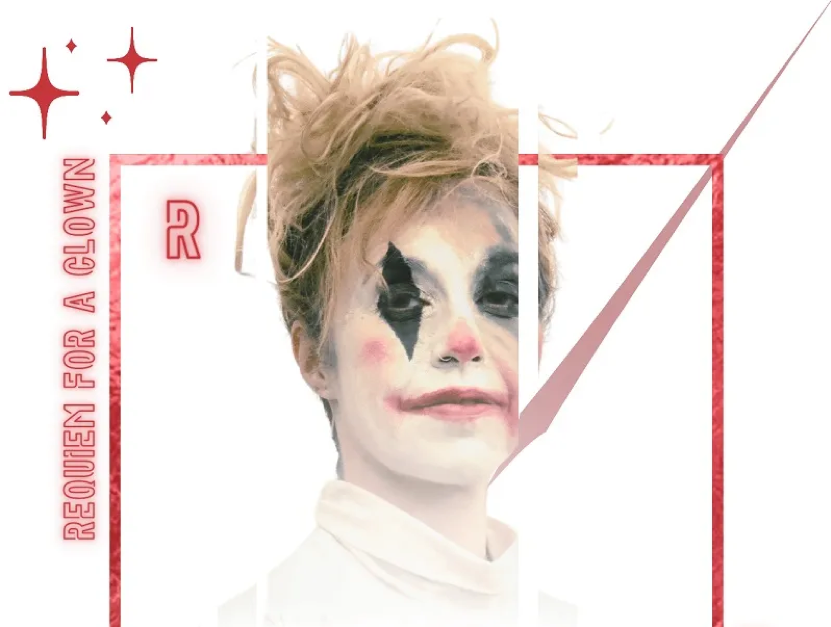

Text Antoine Colla. Performance Rhiannon Morgan. Direction Antoine Colla. Language: French. Luxembourg.

Rhiannon Morgan. Photo et maquillages couverture: Danai Tezapsidou, Diane Demanet Tanios

Requiem for a Clown was written and directed by Antoine Colla, who also designed the lighting, and performed by Rhiannon Morgan with the participation, mainly through the soundscape, of Servane lo Le Moller; the performance depicted the psychic experience of the void, expressed through the fragmentary telling of a fairytale.

The mounting, fragmented narrative was portrayed on stage by the actor’s nearly stationary movements within the frame of a carousel. In that emblematic setting, she referred to pivotal moments in her life, all underpinned by a shared theme: she was the child whom the fairy godmothers never blessed, whom her mother never looked at, and therefore never loved. The two performers moved within the fairytale world, sometimes decorating it, other times making and eating candy floss, in other words, creating an essentially timeless realm where memory is composed of sensations, colors, and the imprints of gazes and traumas that proved indelible.

Beneath the playful aspect of the scenery, threatening developments quietly smolder: the innocent, wounded girl transforms into a repulsive insect. The key phrase, "I’m meant to be squashed" represents the trauma and confirms the initial threat which the spectator senses in the seemingly charming set, while the actor’s impressive movements convey with great sensitivity and finesse the subtle nuances of her confessional narrative.

The live music, the wooden horse, the effigy of a child without facial features and the nightmarishly bare carousel create a stage setting wherein the actor-dancer achieves immediate connection with the audience. She gains not only their aesthetic appraisal vis à vis the performance itself, but also their complicity in the quest for or invention of the self, as realized in the gaze, i.e., the acceptance of the other.

The performance attempts to eradicate the fine line between narrative structure and the engagement of the recipient-spectator, and successfully accounts for the author’s motto:

The clown dissolves the boundaries between self and other,

Holding up a mirror that blurs individual separateness.

In this liminal space,

we see ourselves in the other’s eyes,

reminding us that connection

—both joyous and haunting—

is the essence of life.

(My warm thanks to the author for permission to reproduce her text)

Silêncio, que vai-se cantar o Fado !

Text and performance Magaly Teixeira. Portuguese guitar Miguel Braga, classical guitar Joaquim Caniço. Language: Portuguese. Portugal.

Magaly Teixeira.

The third-generation Portuguese migrant to Luxembourg, Magaly Teixeira, has conceptualized and realized a performance-concert that celebrates the univocally national/Portuguese character. From the outset, the use of folkloric items on stage effectively recreated a typical Portuguese tavern of old, or a migrant household, where the gathering in progress centered on music and specifically, the traditional fados. Paralinguistic references to the high priestess of the fados, Amália Rodrigues were achieved by means of photographs and musical records strewn on the floor, as well as the music itself, and created an emotional bond with the audience and thus created a familiar, communal space.

The songs, as well as the two poems that were read in French and Portuguese, were aimed at the universal language of music. The performers conformed to the classic mise en place of small concert spaces or even household celebrations. This choice confirmed that performance need not always involve the risqué/subversive treatment of a concept on stage, but rather has its origins in an elemental ritual process through which the music and the vocals connect the actors and the audience, eliciting spontaneous emotion.

Although the performance-concert of the Portuguese artists may have been lacking in originality, it most definitely did not lack talent; rather than restricting themselves to the confines of virtuosity, the artists gave expressed a profound nostalgia for their homeland.

All Before Life is Death. An Entertaining Evening Full of Hocus Pocus

Text and Performance Benjamin Verdonck. Language: English. Belgium.

Benjamin Verdonck. Photo: Henk Claassen

The artistic practice of Benjamin Verdonck, actor, writer, visual artist and theatre-maker, staunchly defies classification. His defining mark is the development and actualization of new theatrical forms, especially that of the «tafeltoneel.» The term refers to scenes staged on a table-sized, mobile theatre which can be utilized anywhere, indoors or outdoors, and disappear just as quickly. Here, the props and actions serve to convey the simplicity of theatre and the directness of the actor’s address to the audience.

The performance All Before Life is Death. An Entertaining Evening Full of Hocus Pocus featured doors opening and curtains closing almost imperceptibly, magical showboxes, a number of colored strings, audience participation, placards with caustic but humorous remarks, photographs of Brad Pitt as Trump or war scenes and the performer, his face covered throughout with melting butter, gesticulating in a fashion reminiscent of the aesthetics of silent movies and Buster Keaton or, in parts, his beloved, emblematic butoh master, Kazuo Ōno.

His performative words, both written and spoken, thoroughly political, pointed and ironic, also elicited laughter from the audience in addition to the embarrassment he intentionally provoked through the choice of movement and theme. The title, All Before Life is Death, makes a resounding and tender comment on the notion of failure and the right to reject societal and political decrees. Furthermore, in some parts of the performance, the engagement of the audience, especially the children, accentuated the critical intent and contributed a lighter tone to the grim and pessimistic subject matter.

Rapid one-liners, fragmentary jocular scenes, the extensive use of audiovisual material, and the excess of his gesticular vocabulary combined to create an enigmatic performance with rugged features. Occasionally overbearingly intense, the performance featured a politicized type of humor that challenged the audience of earnest although not overly serious viewers.

Unseen Universes

Choreography and performance Sissy Mondloch. Dance. Luxembourg.

Sissy Mondloch. Photo: Zoë Mondloch

Sissy Mondloch, choreographer, dancer and dance teacher, created Unseen Universes in an attempt to sensitize audiences to the critical issue of the environment and to instigate a meaningful dialogue between the individual and their own inner terrain. She states that her interest lies in the individual’s relationship to their inner world; she endeavors to showcase those psychic landscapes that relate to the exterior world, while expressing and influencing it.

Her choreographic vocabulary and stage setting evoked the four basic archetypal elements which are the material of mythology and physical existence: water, earth, air and fire. In performative terms, her stylistic approach of perhaps intentional naivete successfully revealed the artist’s intention. The unseen universes can become visible through introspection and acceptance of the whole: through its expressive choreography, the body interacts with the environment and the space which contains it, thus affecting its wider context.

The Whore of Canaan

Text and Performance Lana Nasser. Language: English and Arabic. Jordan | Netherlands.

Lana Nasser. Photo: Cees Rullens

I would like to begin my commentary on the performance of L. Nasser, Jordanian writer, actor, performer, voice-artist and dreamworker, with the informative notes she wrote in the script; I am grateful for her trust and generosity in sharing her work with me.

Regarding her dramatic character(s) she introduces:

- AJOUZ:an old androgynous person (He) moves on stage with small steps and a hunched back. (Center light: square)

- THE olive TREE(she/they): several characters of trees and dances – Stationary – enclosed within large spot light. (SR Circle)

- MUSICIAN: live: Oud, Hand-drum, Contrabass, buzuq & sound effects – stationary SL/circle.

- AV: VOArabic poems & Video projections

- LOCATION: A crumbling ancient city on a hill across another hill with the last remaining olive tree – separated by graves.

This information is essential to engage with the performance and experience the pleasure of participating as a member of the audience in such a project.

Next, I cite a summary description of the narrative as it appears in the program and in her personal webpage:

An old man leads you through an ancient crumbling city to the last tree standing- AJΟUZ is her name, Olive. She carries the stories of her kin and tells of her kind. Rooted in memories of people and place. Displaced, exploited and whored, yet still bearing seed.

Her subject surpasses the boundary of a fictive figure with intimations of historical content, aiming for the far reaches of human experience. This is an old man referenced by a feminine pronoun, an androgynous person of manifest femaleness, embodying the memory, the trauma and the luminous aspect of a timeless land. The body gradually becomes a battlefield, a place of healing and a testimonial for what has transpired and exists on record. The physical form alludes to the mythological symbol of the olive tree, wielding the power and the will to reproduce, the ability to know, the capacity to withstand. The performer effectively represented the motif of transformation, using not only characteristic props, such as the large shawl turning to a magic carpet and a veil, but also the well-tuned instrument of her voice and her precise emotive movement, interacting masterfully with the musician on stage, Antonio Alemanno.

Two parallel landscapes thus emerged, the musical and the narrative, in perfect synchronization. The latter moved with poetic discernment between English and Arabic, fueling the methexis with the audience through the action and successive transformations of the whore of Canaan. The androgynous figure, the woman as a city-whore, as a young girl, a fighter, a lover, a victim of abuse, finally becomes a free woman who claims her voice and its power.

This is How You Lose Her

Text and performance Jess Bauldry. Direction Erik Abbott. Language: English. Luxembourg.

Jess Bauldry brought to the stage of Banannefabrik a performance with many familiar elements: a fragmented narrative, elliptical development of themes, and the use of props depicting routine mundane tasks which are transformed during the action on stage, thus acquiring a metonymic interpretation.

The issues she explores as well as the meaning of the title itself suggest a series of questions: “Why can’t we be like the women who have it all figured out? Why is female friendship so complicated? And why does the pursuit of external validation always leave us feeling so empty?”. During the course of the performance, these and other equally poignant questions are presented to the audience, sometimes quite directly, but without offering a satisfying answer that would support key elements of the plot. With woman as the subject of investigation, the performance foregrounds her reflections and resolutions of the problems she faces, as well as the daily friction to overcome obstacles she should no longer have to face. As such, the play offers an interesting yet unoriginal commentary on contemporary womanhood.

The core of her concerns is deftly illustrated by the clever use of props, such as a blackboard on which she jots questions/issues which she then erases when it’s time to move on, and the cardboard boxes which signal the intention to organize her life and her repertory of movement. However, the narrative or discursive development of the key questions raised lacks innovation and an element of surprise that could have been created, had the direction of the piece avoided cliché, which detracted from the actor’s vitality and expressive capability.

Mad World

Text and performance Sarah Lamesch. Language: English. Luxembourg.

Sarah Lamesch. Photo: Carlos Martinez Casanova

In the program of the Monodrama, this performance is listed as theatre, thus alerting the spectator to its formal differentiation from the other genres listed in the program as performance, dance, concert/performance etc.

The actor and creator of this monologic event addresses the subject of deviation, as intimated in the resounding title of her work. She explores the rupture from normalcy as the result of a traumatic experience, a painful separation, an uncertain precarious tenderness, the thought of no longer belonging to the familiar place of relationships and a life that unfolds in tandem with the other. The trauma proves so intense that it destabilizes her psyche and calls into question the realm of memory. By questioning the veracity of events, it also questions truth as a value and condition of communication; the question she raises is “How can you be sure of what really happened, and what was only in your mind?”

No answer is offered, however, as the actor/performer foregrounds, through her voice and movement, aspects of dramatic relevance for the spectator. Although she chose a monotonous expressive key which impacts the delivery of her monologue, Lamesch delivered a convincing interpretation of her character’s psychic fluctuations. Similarly, the costume choice of overalls, reminiscent of a hospital setting, helped shape the microcosm depicted on stage and served as a metonymy for our culture of separations and the unsettling darkness of our times.

Does It Bite?

Text and performance Olga Pozeli. Language: English. Greece.

Olga Pozeli. Photo: Kostis Davaris

This work by Olga Pozeli, actor, director and founder of the theatre group Noiti Grammi, raised a seemingly innocent but ironic question: “Does it bite?”. The scenic space, filled with moving stuffed toys and a fish thrashing in the hands of the performer but otherwise resembling a household pet, seems to be asking which life has more value, that of a human or an animal. Who decides what is wild, tame or socialized and whether or not a life should be spared or terminated? Should we speak of crimes against the environment when we engage in unchecked hunting or livestock farming, and should we dare to label them as genocide?

Pozeli’s monologic performance problematized the consumerism and brutality of the modern world. The political nature of her performance was revealed in the alternate use of music and speech, the video projection of cages and the execution of self-mocking and caustic choreography.

There was no attempt at didacticism nor at providing a one-sided answer to the question, “Does it bite?”. Nevertheless, the performance was successful; with its aesthetic of minimalism, interactive relationship with the audience, eloquent movements of the actor and telling use of props, it encouraged us to consider the animal we used to be, the life we have and our choices and responsibility regarding the imprint we wish to leave behind.

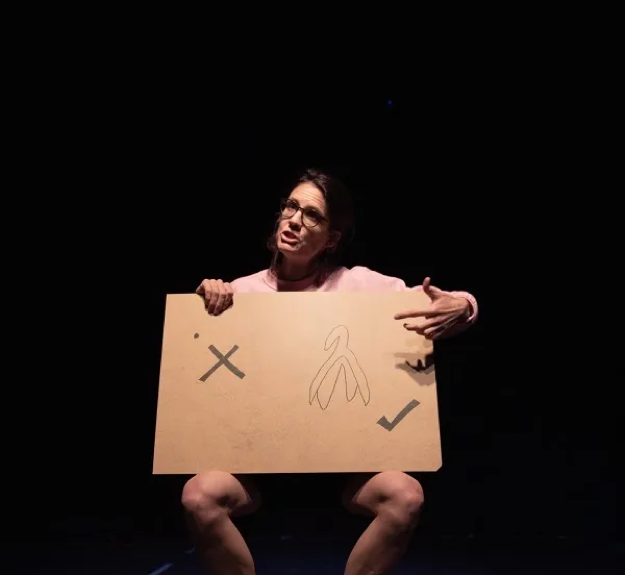

This is my Truth, Tell me Yours

Text and performance Jasna Žmak. Language: English. Croatia.

Jasna Žmak. Photo: Sanja Merćep

The title of this solo project of dramaturgist-writer Jasna Žmak alerts the spectator to her confessional intention. She begins by exploring her relationship to the realm of the arts, directly disputing their effectiveness in terms of social responsibility, and initiates a discussion of whether or not it is possible for art to intervene in contemporary society. Despite the range and seriousness of her subject matter, her performance does not resemble a lecture, especially as it involves intense physicality. In 2011, after firing a stage gun during the performance MandićMachine, directed by Bojan Jablanovec and performed by Marko Mandić, Žmak started experiencing tinnitus and extreme sensitiveness to noise, giving her work a greater depth whereby physical experience came to define her artistic endeavor.

Although seemingly unrelated, the subjects of tinnitus, sexual freedom, pleasure and patriarchy are taken up as major organizing themes. Using aspects of stand-up comedy, the artist poses questions to herself as well as the audience on the significance and meaning of sexual freedom, guilt, the incrimination of pleasure and artistic production in the era of relentless capitalism.

While her physical movement was relatively awkward, her intention to communicate with her audience was successful as her humor and immediacy compensated for her acting weaknesses. Her rapid-fire speech became the defining trait of a confession marked by the frequent use of a blanket on stage, signifying her desire to isolate and shelter herself from the disparaging gaze of others. Similarly, she created a familiar, polyphonic environment by using a laptop from which the voices of her partner and her best friend could be heard, thus enhancing Žmak’s aim to speak of truth and the abolishment of shame.

Je suis à prendre ou à laisser

Text Bérékia Yergeau. Performance Rebecca Kompaoré Tindindé. Language: French. Republic of Congo

Rebecca Kompaoré Tindindé. Photo: Romaric Ibrahim

This performance, confronting the audience with a range of challenging contemporary issues, was directed by Abdon Fortuné Koumbha from Congo, based on the text by Haitian poet and director Bérékia Yergeau and interpreted by the Ivorian Rebecca Kampaoré Tindindé, a multifaceted artist and writer. The main character of the monologue, Angela, has to leave behind the small city where she was born in order to find fame and a promising career, once her incredible vocal talent is acknowledged. Complicating her life further, her manager constantly pressures her to change her way of dressing, her distinctive curly hair, her personal style and even her skin tone.

The performance was structured around a powerful bipolarity defined by key sets of opposing terms, such as village-capital, authenticity- alienation/star system. The upcoming artist is told to give up her simplicity and honesty and to adopt instead the artificial look of a Beyoncé and transform her skin color and stylized appearance. She chooses, however, to clash with the system, defending her personal style and ethics when she says: “You’d promised me I would become someone, not someone else.”

The performance combined elements of stand-up comedy and a denunciatory monologue, and was brought to life by the rhythm and music foregrounding the character’s achievement. Also, of interest was the visual aesthetic enhanced by the effective use of lighting, props and settings, taking us first to a bar and then to a company office, with the manager’s empty jacket hanging in mid-air, full of connotations.

Rebecca’s performance was spontaneous and immediate, despite a certain excess of gesture and a somewhat aesthetically one-dimensional address to the audience. She succeeded in highlighting the value of music as a major component of cultural creation, and validated the worth of the artist, especially the woman-artist, beyond the strictures of lifestyle.

Goethe’s FAUST

Adopted and performed by Max Pfnür. Direction Benjamin Blaikner. Language: German. Austria.

Max Pfnür. Photo: Benjamin Blaikner

On the final afternoon of the Monodrama Festival, the talented and widely acclaimed actor Max Pfnür presented an adaptation of the ingenious Faust. In a remarkable solo performance lasting five hours, with only two brief intermissions, he played all the roles himself. His performance was beautifully supported by Benjamin Blaikner’s direction and the sophisticated music of Roli Wesp. Regrettably, an urgent return to Athens prevented me from witnessing this monologic tour de force and experiencing Goethe’s singular and ever-relevant text in this extraordinary interpretation.*

All in all, I am privileged to have experienced ten days, ten countries and fourteen stage events with dozens of artists taking part in the monologic festival with its many years of experience and contribution to international culture. The 15th Monodrama Festival 2025 once again brought together the arts of performance, conventional monologic form, stand-up comedy, devised theatre and music composition, and it enriched the city of Luxembourg by showcasing instances of an active dramaturgy and an ongoing communication without borders, free from barren aesthetic classifications.

* Eleni Gkini holds a Ph.D. in French Theatre from the University of Athens, specializing in Philosophy and Philology. She teaches Theatre Theory in the Postgraduate Program at the Open University of Cyprus. As a dramaturge, she collaborates with Persona Theatre Company (persona.gr) and other theatrical groups. Eleni regularly participates in international theatrology symposia and is an active literary translator, working from French and Spanish into Greek across genres including drama, prose, and poetry. Her publications include the monograph Monologues Inspired by Ancient Greek Tragedy: Signs and Intertextuality (Athens: Dodoni, 2022).